Heracles Panagiotides: Are you good?

by Heracles Panagiotides, University of Washington Seattle

Have you ever asked yourself the question: “Am I good?” What does it really mean to be good? People have a moral perception of themselves and others as being good, bad or anything in between. These opinions are based on behaviors that form value judgements. Unfortunately, perceptions betray reality. Jesus once made a surprising comment to someone who called Him “good”: He said “No one is good, except God alone”, implying that all people are not good. So, what does it mean to be or to not be good? Is goodness simply an overt or covert moral attribute? Is goodness the absence of any moral transgression? In that sense, all people are bad, since moral blemishes exist in all of us. If we were to perceive goodness as a moral defiance alone, then behavior should be enough to define goodness.

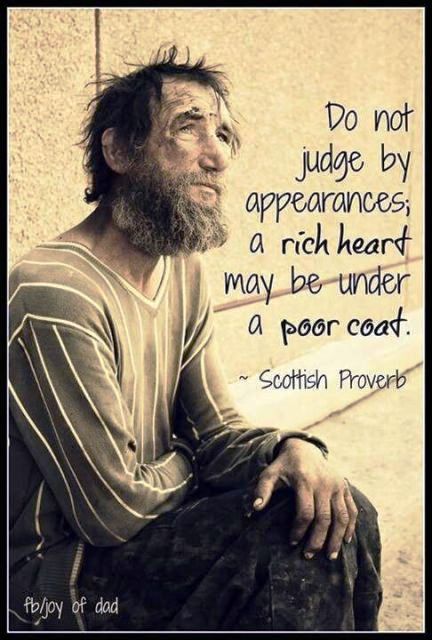

There are, however, deeper aspects of self, such as desires, thoughts, feelings that act as conscious or non-conscious forces in all of us driving us in unforeseen negative directions. Conversely, people of ill repute and conduct, at some point, might exhibit surprising goodness. It might be more realistic then to think that we possess good or bad qualities leading us toward either goodness or malice. We are in a state of constant flux, moving in healthy or unhealthy directions.

There are, however, deeper aspects of self, such as desires, thoughts, feelings that act as conscious or non-conscious forces in all of us driving us in unforeseen negative directions. Conversely, people of ill repute and conduct, at some point, might exhibit surprising goodness. It might be more realistic then to think that we possess good or bad qualities leading us toward either goodness or malice. We are in a state of constant flux, moving in healthy or unhealthy directions.

It is the direction and state of spiritual health that define the inner dynamic of a person. Both of these qualities, however, remain hidden from others and often from ourselves. We only see behavior, while there is a disconnect between these inner realities and overt actions. Let’s ignore behavior and its properties for now, and focus on the reality of inner health. What is spiritual health? We can examine it on a descriptional, on a definitional, and on a causal basis. The description of an illness is symptomatic. The symptoms of a physical illness are, for example, pain, fever, etc. Signs of spiritual sickness are (a) pride and jealousy, (b) anxiety for material or sensual desires and (c) delusional fantasy. Conversely, signs of spiritual health are inner peace, love and fulfillment.

One might rightly argue that what I have listed as symptoms of spiritual illness have a biological basis. This is often the case. Many forms of mental pathologies have biological causes. However, I believe that much of it has deep spiritual sources. A careful examination could reveal their true causes. Unfortunately, modern medicine undiscerningly treats such symptoms as if they are always physical in nature, i.e., through medication. They see “results” on the surface, but ultimately doing disservice to the person. Of course, biological psychopathologies exist and they require pharmacological treatment. Spiritual illness, however, also exists and requires spiritual healing. As with physical illness, we define illness in terms of pathophysiology, spiritual illness is similarly defined in terms of its own pathophysiology: fragmentation of self, spiritual starvation, both leading to atrophy or darkening of spiritual senses. Each one of these factors warrants separate examination.

Fragmentation of self. The original state of self is to be simple. We see this in children. The younger they are, the simpler their minds are. They have an element of innocence that is eventually replaced with complexity as they grow older. I am not referring here to cognitive complexity for problem solving, but the simplicity of how they view themselves and others. A psychologically sophisticated person will object that this is a factor of brain maturation resulting in what psychologists call “theory of mind”, a term referring to one’s ability to theorize or speculate what is in another person’s mind. The simplicity I am talking about is not in the perceptual domain, but in the interpretive, attributing motivation in spite of perceptual sophistication. Thus, simplicity becomes a question of not what is in a person’s mind, but why the other person is thinking or acting a certain way. There is a huge difference between the two.

Thus, the actual self is eventually separated from the perceived self, creating confusion in a dissonance between real and artificial or idealized self, often resulting in a form of identity crisis expressed in the existential question of many young people: “Who am I?” The confusion is extended to how others ought to perceive us, as if seeking validation for the new idealized self from others. The identity crisis further increases the vastness of the chasm between the two selves, becoming greater with age. Eventually, the real self is forgotten and bound in the darkest recesses of oblivion, neglected and ignored. The consequences of a neglected self are enormously underestimated.

Spiritual starvation. The spirit needs nourishment like the body needs nourishment in order to continue its healthy function. God is the only source of spiritual nourishment for the spirit. Spiritual neglect has two catastrophic results, (1) starvation and (2) seeking to satisfy our hunger with unhealthy substitutes. This in the language of Eastern Christian spirituality is called ακηδεία, best translated as lack of caring for the spirit leading to the vicious cycle of pleasure-pain. We seek to replace spiritual nourishment with physical pleasures; pleasures lead to pain, while pain leads to seeking more pleasures, and thus the cycle. Physical pleasure is not the only substitute. An interesting phenomenon of our days is being in a state of continuous sensory stimulation through electronic gadgets. I frequently see people being in the physical presence of others but disengaged and isolated, absorbed in their iPhones, iPads, etc., as if in a desperate and immediate need to feed their minds through the senses. Television, telephone gossip, and nowadays the internet are examples of unsuccessful attempts to feed the spirit.

Darkening of the spiritual senses. This aspect of spiritual illness is less obvious and foreign to most. The experience of spiritual realities is a concept so alien to us that is either considered fraudulent, or at best so theoretical or removed, that it has no bearing with any personal experience. It is only a legendary quality attributed to few. Spiritual senses exist in the same way that senses outside the spectrum of human experience ranging from vision, hearing, a sense of direction and chemical senses exist in others species. Eastern Christian spirituality speaks about the existence of spiritual senses parallel, so to speak, to the physical senses. In that context, there is spiritual vision, spiritual hearing, etc. They exist in all of us, atrophied in most. They are evident in a few enlightened people. Spiritual senses transcend space and time.

Enlightened people “see” beyond physical boundaries, into the past and into the future, as if space and time have collapsed. They “see” and “hear” realities of another world that they reveal to common people. Sometimes they are in the presence of a supernatural light that others might see. These senses are the bridge between the mundane material world and God’s world. The absence of spiritual sensory experience creates a vacuum that man attempts to fill through imagination and reason. Imagination harbors dangers. Illusionary thinking, in spite of rationality, leads to the deception and dangers of ideology. Imagination based ideology is not convincing. It paradoxically attempts to convince others through any means, often unethical and violent, for one reason only, to reflectively persuade the otherwise unconvinced self. It is worth noting that unhealthy imagination also becomes a vehicle for faulty identities, desires and anxieties discussed in the previous paragraphs.

Following the description of spiritual pathologies, we can now take this inquiry a step further and look at causes. Man’s ontology, his identity, fulfillment and his knowledge of self, others and the material world depend on his organic relationship with God. When this relationship is severed, it results in the disease of sin. This brings us to the original statements of morality. It is not constructive to look at sin as a moral or legalistic transgression, but as the Greek word αμαρτία means, “missing the mark”. The mark is man’s functional relationship with God. God is simple, and man is meant to be simple. God is love, and he nourishes His children. God is Truth and enlightens those who are existentially connected with Him. In one word, God is the source and cause of man’s wellbeing and spiritual health.

It is possible to bring restoration and healing to our ailing spirit, to reverse the process of spiritual and eventual material decay, to return to God through a creative effort. It is only accomplished through metanoia and requires purification of the heart. Purification will lead to illumination, i.e., restoration of the spiritual senses. Illumined people have pointed at this process. It is a function of two conditions: man’s effort and God’s healing intervention. Man tries to reverse the process through ascetic practice, such as fasting, stillness, reflection and prayer. It is worth thinking at this point about one of these ascetic practices, fasting. It is not just a ritualistic cleansing, it is not a dietary tool, not even an exercise in will power. Through proper fasting, we create a material vacuum in order to fill it with the missing and desperately needed spiritual nourishment. A lot more can be said, and has been, about ascetical practices.

The other component of purification is a divine component called Grace. Man alone cannot accomplish this. It is only through the synergy between our human effort and Grace that purification can be accomplished and lead to illumination of the heart and the spiritual senses. Illumination, however is not the final destination. If it were, it would lead back to man. The purpose of our journey is to become deified, to become holy. This is a difficult concept to comprehend. We know that there are people we call Saints who reached this level. But we do not have a conventional parallel concept to relate to. The great Apostle Paul spoke of ascending to third heaven and heard words impossible for man to utter. Deification is an experience beyond words and entirely foreign to anything most of us have ever known. In the same way that our approach to God is apophatic, deification and holiness is also apophatic, beyond description and understanding for the uninitiated.

Saint Gregory, Archbishop of Constantinople, a 4th century Father of the Eastern Church, defined man as ζῶον θεούμενον, as an “animal in the process of becoming deified”. This is the direction of which I wrote earlier. This direction is the component that defines our existential state of health. Indeed, we are in a state of continuous flux, in a state of becoming. We cannot see the human spirit outside this inner motion. Any static appraisal lacks a pragmatic evaluation of the reality inside all of us.

- Hits: 5424