1999. Illness, Cure and the Therapist according to St. John of the Ladder

The Rev. Metropolitan of Nafpaktos and St. Vlassios Hierotheos

THE GREEK ORTHODOX THEOLOGICAL REVIEW Vol. 44, No,. 1.4, 1999

Today, there is a lot of talk about the cure of man, since we have realized that, by living an individualistic way of life, separated from community and reality, obliged to live in a tradition that has lost its communal character, where there is no communion and preservation of the person, man is sick. Naturally, when we talk of illness we do not mean its neurological and psychological aspect, but we mean illness as the loss of the true meaning of life. It is an illness that is first and foremost ontological (i.e. to do with our very being).

The Orthodox Church seeks to heal the sick personality of man and indeed this is the work of Orthodox theology. In the Patristic texts we see the truth that Orthodox theology is a therapeutic science and method: on the one hand, because theologians are those who have acquired personal knowledge of God, within the context of revelation, and thus all the powers of their soul have been already cured by the Grace of God; on the other hand because these theologians, who have found the meaning of life, the true meaning of their existence, go on to help others in their journey along this way, the way of theosis.

In attempting to study human problems we come to the realization that at their very depth these problems are theological, since man was created according to the Image and Likeness of God. This means that man was created by God to have and to maintain a relationship with God, a relationship with other people, and a relationship with the whole of creation. This relationship was successful for first-formed human beings, Adam and Eve, precisely because they possessed God's Grace. When, however, man's inner world became sick, when human beings lost their orientation towards God and consequently God's Grace, then this living and life-giving relationship ceased to exist. The result of this was that all his relationships with God, with his fellow man, with creation and with his own self were upset. All his internal and external strength was disorganized. He ceased to have God as his focus, and instead he replaced him with his own self. A self, however that was cut off from those other parameters became autonomous, resulting in him becoming sick in both essence and reality. Therefore, in all that follows health is understood as a real and true relationship, and illness, as the interruption of that relationship, when man falls away from his essential dialogue with God, his fellow men and creation, and sinks into a tragic monologue.

To use an example, we (could say that before the Fall man's center was God. His soul was nourished by God's Grace and his body by his grace-filled soul. This was something that had consequences for all creation, and in this sense man was the king of all creation. However, all this balance was disturbed by sin. The soul, having ceased to be nourished by God's Grace, now sucks at the body, and thus the passions of the soul come into being (egotism, pride, hate etc.). The body, having ceased to be nourished by the soul, now sucks at mate-rial creation; hence the bodily passions (gluttony, possessiveness, desires of the flesh etc.) are created. In this situation nature both suffers and is violated, since, instead of receiving God's Grace through the pure looking-glass that is man's nous, it is exposed to violence by man, because what man wants from it is to satisfy his passions. Hence, ecological problems are created. After the Fall, a complete reversal is noted in man's relationship with God, with other people, and with creation. This is and is called an illness, a serious sickness. The cure for this, as seen within the Orthodox Tradition, is the proper reorientation of those relationships, the rebuilding of human existence in a way that man's center is God once again and that man's soul is again nourished by God. When this happens the Divine Grace is transmitted to the body and from there it is conveyed to the whole of irrational creation.

In light of this, man's problems are not simply psychological, social and ecological, but problems of relationships and universal responsibility. They are ontological problems, i.e. problems pertaining to man's being and existence. It is within this framework that we have spoken about the illness and cure of man in the Orthodox Church and about theology as therapeutic science. The Orthodox Church does not reject medical science. On the contrary she accepts and uses medicine in many instances. At the same time she looks at the ontological dimension of man's problems and tries to bring man back to his right perspective and to his original ontological orientation. Hence, we can talk of spiritual psychotherapy and of essential psychosynthesis but not of psychoanalysis. From this standpoint, even someone who is healthy from a psychiatric point of view can be sick from a theological one.

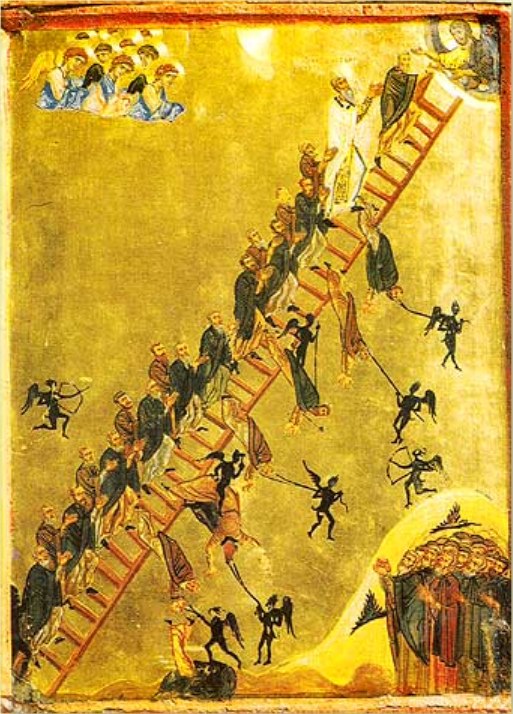

The saints of the Church also worked within this framework. Amongst them is St. John of Sinai, the author of the well-known book The Ladder, which has this title because it has to do with the ladder of man's ascent to God. This ascent is in reality a reorientation of man's true relationships with God, with his fellow man, with creation and, naturally, with his very self. All that follows must be placed within this essential framework.

1. THE PERSONALITY OF ST. JOHN OF SINAI

St. John of Sinai lived in the area of Mt. Sinai in the sixth century. He became a monk at the age of 16 and thereafter lived the strict ascetic-hesychastic life. Towards the end of his life he also became the Abbot of the Holy Monastery of St. Catherine, but he finally withdrew to the desert, which he had loved so much throughout his life.

St. John of Sinai lived in the area of Mt. Sinai in the sixth century. He became a monk at the age of 16 and thereafter lived the strict ascetic-hesychastic life. Towards the end of his life he also became the Abbot of the Holy Monastery of St. Catherine, but he finally withdrew to the desert, which he had loved so much throughout his life.

St. John's biographer gives us some information about his life. He mainly presents us, however, with how he proved to be a second Moses who led the new Israelites from the land of slavery to the land of promise. By eating only a little food he crushed the horns of arrogance and vainglory, i.e. of those passions which are difficult to be discerned by men who are wrapped up in worldly occupations. By cultivating stillness of both nous and body, he extinguished the flame of the furnace of fleshly desire. With God's Grace and his own struggle he was freed from slavery to idols. He resurrected his soul from the death that threatened it. By mortifying all attachments and by fixing his perception on the immaterial and heavenly realities, he was able to cut off the bonds of sorrow. He was completely cured of vainglory and pride.

It is evident here that St. John of Sinai made a great personal effort to gain the freedom of his soul and his emancipation from the tyranny of the senses and the sensible, so that all his faculties would function according to nature and even stretch beyond nature. His nous was freed not only from the mastery of passion, but also from the fear of death.

Indeed, he demonstrated that stillness of nous purifies the nous from various external influences, and then man becomes clairvoyant and foresighted and can perceive the problems that exists in other people and in the world. When this is achieved, then the purified nous finds itself in another dimension and sees things clearly. Just as various medical instruments can diagnose the illnesses that exist in the body, so the pure nous of a Saint can see the state that exists in the innermost part of the soul. He possesses great penetrative perception, but also tenderness. Although he probes and sees the depths of being, by the Grace of God, he still embraces man with tenderness and love. On this point, the saying of the Old Testament, "The earth was without form and void and darkness was on the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved over the water," could have been put into practice, in one way or another. The deep, or the abyss, is the heart of the sick man, yet the Spirit of God moves over it, with tenderness and love in order to form a new creation.

The greatest obstacle to man's cure is the confusion of man's nous with the idols of the passions and with external forms. In this condition, man sees things through a divided prism and, of course, he fails to help people who are wounded and search for truth and freedom.

St. John of the Ladder acquired such a pure nous, not by studying at the great centers of learning of his day, but by learning from the stillness of the desert, where the passions particularly howl and seek to accomplish man's destruction. His nous became godly and God-like. Thus, St. John became the pre-eminent man formed by God and renewed by the Holy Spirit in Christ Jesus. He did not impart human knowledge to us, and wise ideas, with all that he wrote, but his very being and for this reason his words are disarming and therapeutic, but also contemporary.

St. John's Ladder is in continuity with the hesychastic texts of the great Fathers of the Church, the first systematic analysis of the illness of the human soul and of man's restoration to spiritual health. He constructs an admirable and successful psycho-synthesis of man's personality. Likewise, this essential work is continued later by other Fathers of the Church, such as St. Maximos the Confessor and St. Gregory Palamas. Centuries before the psychoanalytic theories of various psychiatrists, psychoanalysts and psychologists had been formed, the Fathers of the Church and St. John Climacus in particular incised man's soul in order to reunite it. Their research was limited to the depth of the self, since, truly, when someone understands the problem of evil within his own being, without trying to hide it, then this person realizes all the power of evil that exists throughout creation.

We will go on to study some extracts, but not make a complete analysis, of his well-known words "to the Shepherd." [ 1 ]

2. THE PRIEST AS THERAPIST

In an earlier book of mine, in which I wrote about Orthodox Psychotherapy, [ 2 ] I first tried to explain that Christianity and especially Orthodox Theology is a therapeutic science. I did this before examining what sickness is and before analyzing the sickness and cure of the soul, the nous, the intelligence, the passions etc. Indeed I prefaced it all with a chapter on the priest as therapist. Some of the readers said that I should have written first of all about cure and then go on to write about those who cure.

Giving first place to the priest as therapist had its own importance, since only a clergyman who has obtained the necessary capacity of knowledge, of experience and especially of his own existential health, can put to correct practice the teaching of the holy Fathers and cure the people. If a priest is not a therapist, as required by Holy Tradition, then he can prove himself to be hard and senseless, even if he uses the teachings of the Holy Fathers of the Church. This means that in the name of therapy, or salvation, or stillness (hesychia), such a priest can actually lead man to a spiritual dead end. In other words, when an incapable and inept priest uses biblical and patristic texts, he makes them mere ideological or even moralistic texts with terrible consequences for man's soul and higher calling. Such a bad use does not transfigure impassioned man and does not lead him to discover the original proper relationship.

According to St. John of Sinai, a priest who undertakes the therapy of a man must be capable of that work. He must possess the appropriate qualities and must have acquired a living experience of God within the boundaries of his own personal life, beforehand. Indeed, examining first the work of a good priest St John uses many terms, employing images from his own time. A clergyman who guides other people is a "Shepherd," a "Pilot," a "Physician," a "Teacher" (2, 3, 4, 5). These four attributes are closely linked to each other, since they are related to different duties that a priest must undertake. There is, therefore, a mutual «intercommunion,» as it were, between these four attributes.

The Shepherd presupposes a rational sheep, which must be suitably fed; the Pilot presupposes a ship, sailors and the sea, a Physician presupposes patients and a Teacher presupposes the unlearned who must learn. Thus, the Shepherd is simultaneously a pilot, a physician, and a teacher; the Pilot is a shepherd, doctor and teacher; the Physician is a shepherd, pilot and teacher and the Teacher is all the aforementioned.

In using these images, however, St. John of Sinai also compares the corresponding virtues that should distinguish the Priest. The Shepherd must seek out and heal his sheep "by guilelessness, zeal and prayer."(2) The Pilot is the man who "has received noetic strength from God and from his own toil." (3) The Physician is the man who has no sickness of body and soul and needs no medicine for his health (4). The Teacher is the one who has received a "noetic table of knowledge," a light whereby he has "no need of other books," because, according to St. John, it is unseemly for a teacher to teach from copies and manuscripts, just as it is unseemly for painters to teach from old paintings (5).

These images, as well as the attributes linked to the images used, show that the Priest-therapist must himself be cured, to the extent that this is possible. That is to say, he must have a proper orientation, to have personally acquired the living experience and knowledge of God, so that he can help people by means of his own experience. It is not a matter of human faculty and action, but of a theanthropic action, of a help that comes from God, which acts through the particular therapist priest.

In any case, it must be underlined that, of all these images, the one that prevails throughout the whole text of the book the Ladder, but also in the particular chapter that we are studying, is the image of the physician. The Priest must heal sick people, and that does not happen with human knowledge, but through the energy of God and the priest's synergy with him. For this reason St. John of Sinai says: "A good pilot saves the ship and a good shepherd quickens and cures his ailing sheep."(7) Some men "have undertaken unreasonably to shepherd souls" (56), without considering the responsibility of this work and certainly without having their own personal experience. It is throughout the whole of St. John of Sinai's text that we find the qualities and gifts that should adorn the priest-therapist. We will refer to some of them.

First of all, it is stressed that therapy is not a human but a divine task, which, of course, operates with the consent given freely to this work by the priest himself. He says that there are some who "have perhaps even received the power to take spiritual responsibility for other men," yet despite this they do not gratefully undertake this work for the salvation of their brother (59). Nevertheless, only the person who has experienced God's mercy is able "to benefit the sick in an unobserved and hidden manner" (53). Since the cure of man does not occur by human means, but by the Grace of God, for this reason the cure very often occurs hidden and unobserved. From God, the Priest becomes the spiritual steward of the souls. (71)

The arrival of God within man's heart, and particularly that of the priest-therapist, has evident signs, since man is spiritually reborn. An expression of this rebirth is to be seen in the spiritual gifts, which are truly "gifts" from the Holy Spirit. These include: humility, which, however, if excessive can create problems for those undergoing therapy (85); patience, exempting, of course the case of disobedience (84); fearlessness in face of death, for "it is a disgrace for a shepherd to fear death" (67); submission to labor and deprivations on behalf of those being healed (76); inner stillness (88), for then he will have the ability to see sickness and to cure it.

The spiritual gift which is above all other gifts is that of love, because "a true Shepherd shows love, for by reason of love the Great Shepherd was crucified"(24). Moreover, all of this is necessary, precisely because those being educated and healed see the Shepherd as their physician, "as an archetypal image" and all that is said and done by him "is considered to be a standard and law" (23).

In his texts St. John of Sinai often talks of dispassion, which should distinguish the therapist. "Blessed is freedom from nausea among physicians. and dispassion amongst superiors"(13). It is terrible for a physician of the body to feel a tendency to be sick when healing bodily wounds, but it is even more terrible for a spiritual doctor to try and heal wounds of the soul while having the passion himself. Truly, the person who is completely purified of the passions will judge people as a divine judge (96). A clergyman should be dispassionate, since "it is not safe for a man still subject to passions to rule over passionate men," just as it is not right for a lion to graze sheep (47). Of course, St. John of Sinai maintains, precisely because he knows that therapy is not simply a work of man, but the result of God's energy and man's synergy, that for this reason God often works miracles through simple and impassioned elders (41-51).

When St. John of the Ladder talks about dispassion, he does not mean the deadening of the passionate part of the soul, which is a doctrine of Stoic philosophy as well as other eastern religions, but rather the transfiguration of the powers of the soul. That is to say, in the state of dispassion, the powers of the soul, i.e. the intelligent, the incentive and the appetitive powers, move towards God, and in God they love the whole of creation. Therefore, it is not a matter of inertia, but a movement of all the psychosomatic powers.

Dispassion is necessary for the therapist, because, in this way, he is given the ability to judge and to heal, with discernment and good sense, and because the senses of his soul are disciplined "to discern the good, and the bad, and the median" (14). That is to say, he knows when an energy comes from God and when it comes from the devil, because he can make a distinction between the created and the uncreated with great therapeutic results for his patients. A clergyman also knows when to be humble before the person who is being healed and when not to be, for "the superior should not always humble himself unreasonably, nor should he always exalt himself senselessly" (38). This, of course, depends on the disposition and the condition of the patient. Some get benefit from the Shepherd's humility, others are harmed by it. We shall see the value of the virtue of discernment further down, when we examine the ways of treatment that the discerning therapist employs.

St. John adapts the situation and position of the Priest-Therapist to that of the position and situation of Moses. Just as Moses saw God, rose up to the heights of theoria (vision), conversed with God and then went on to lead the people of Israel from the land of Egypt to the land of promise, facing a whole variety of problems and manifold temptations, so also does the therapist. He must have the spiritual condition of Moses and with his own outlook lead the people of God to the Promised Land (100).

This image and adaptation reminds us of the fact that the aim of Orthodox therapy is man's theosis and not some psychological balance. This work then is done by a clergyman whose soul has been united with God and therefore "stands in need of no other word of instruction, bearing the everlasting Word within herself as her Initiator, Guide, Illumination" (100). The whole of St. John's text does not operate on the human level, but on the divine. It does not refer to cases of psychological and neurological illness, but to people who want to satisfy their own inner actuality, which is the fulfillment of the aim of their creation, i.e. theosis. It is precisely this aim that constitutes man's greatest hunger and thirst.

3. MAN AS A SUFFERER OF SICKNESS

The illness of body and soul and the existence of a therapist priest undoubtedly presupposes a sick patient. Earlier on we defined somewhat the illness of the soul, by turning to St. John's book The Ladder and more particularly to the chapter entitled "to the Shepherd." St. John discusses this matter extensively and we should look at some of the characteristic attributes of a sick person.

As we said earlier, spiritual illness presupposes the loss of communion with God, the disturbance of man's relationship with God, with other people, and with the whole of creation, and certainly the distortion and ailment of man's spiritual and bodily powers. Therefore, the sick man sees his illness in his relationship with God and with others when he identifies God with an idea or his imagination, when he uses others for his own gain, when he violates nature and thus displays his own spiritual sickness.

In referring to man here we mean of course his whole composition, the whole substance of the human constitution, soul and body, since man is made up of both, not just soul, nor just body. This means that there is a mutual interaction and influence between soul and body. The illnesses of the soul are also reflected in the body which is joined to it, just as physical illnesses also have or can have consequences for man's psychological world. Therefore, when man cannot satisfy his existential hunger, which is to fulfill the deepest aim of his existence, then his whole being, even the body itself, suffers and is wounded. Complaints, dissatisfaction, anguish, anxiety, despair are related to the lack of fulfillment of man's spiritual quest.

St. John refers first to man's spiritual slavery. God formed him free and yet he fell into slavery, a spiritual slavery to the devil, sin and death. This is like the case of the Israelites who were ruled by Pharaoh and were in need of liberation. In his excellent comparison of the situation of a wounded man to the situation of the Israelites who were in the land of Egypt he talks of man's "mortal sheath." Indeed man hides in himself a deadening passion, a "pollution of brick-making clay," for man fell from the high things for which he was created into earthly and humble things. He also mentions the red and burning sea of fleshly heat and focuses on "every manner of darkness and gloom and tempest," on the "thrice-gloomy darkness of ignorance," on the "dead and barren sea," and also on the adventures of the desert (100). Quite often during the course of his life man finds himself before tragic circumstances, which keep him captive, terrible despair and all of this comes from his existential emptiness his remorse and the problem of death in every sense of the word.

All this makes man suffer torments and feel very hurt. He senses a sickness simmering within his being. Also looking at this through the image of the sheep, man considers himself to be an "ailing sheep"(7). It is a matter of "defiled souls, and especially defiled bodies" (72) which need cleansing, of people who have fallen to the earth instead of rising up towards that which is above. These people are not satisfied with mere human teaching but need one that is much more heavenly. Indeed "lowly instructions cannot heal the base" (6). There are many teachers and psychotherapists with a human perspective who cannot relieve a psychosomatically wounded man who is called "rust" (53), because he suffers and remains "in distress" (76). People see "their own cowardliness and infirmity" (41) within themselves, feel that they are like "small children" and "very weak" and so become sorrowful and distressed (93).

All these descriptions display a man who is tortured and tormented, completely traumatized. St. John of Sinai is not referring here to cases of neurosis or psychosis, but to cases of people who feel that they are failures in life. These are people who did not satisfy their earthly goal for they did not fulfill their deeper existential aim, i.e. their relationship and communion with God, which is the ulterior motive of his question.

Nevertheless St. John of Sinai does not limit himself only to general descriptions, but goes on to make other deeper diagnoses. He sees man suffering in the inner most parts of his soul. These are not skin-deep, physical illnesses, but internal ones that occur within the depths of the soul. Thus he calls man a "sickly of soul" (80), infected with spiritual drowsiness (8). Man feels a terrible burden of thoughts within his soul (93) torturing him and desperately seeks his deliverance.

Again, we must say that this is not about external and abstract states but about internal and specific impurities. Man has full knowledge of these states but cannot free himself. He needs God's intervention, with the help of an experienced spiritual therapist. Thus St. John writes somewhere: "Those who are ashamed to consult a physician cause their wounds to fester, and often many have died."(36)

People in this category are embarrassed to reveal the wounds of their soul and because of this they reach the point where their wounds become rotten and lead them to spiritual death. For this reason the patients must reach the point of revealing their wounds to an experienced physician they trust (36). It is a fact that within the soul there is an "invisible uncleanness" which cannot be seen by the naked eye. This is an internal impurity consisting of putrid members that need healing and cleansing (12).

This means that man does not need his therapist for psychological support and for a skin-deep cure. He does not need his priest in order to satisfy his religious needs, but he needs him to intervene in his own internal world, with discretion and love, with the Grace of God and his own freedom, and to cure man's uncleanness, through his own lack of nausea. This therapist, who through his purity is familiar in his own personal life "with wiping away the filth of others and cleansing them by the purity granted from God, and from things defiled offering unblemished gifts to God," proves himself to be a fellow worker with the spiritual and bodiless powers (78). The spiritual therapist approaches traumatized man with care, sensitivity and tenderness, fullness of love, knowledge, but mainly with the Grace of God. He does not toy with the salvation of another, nor does he mock the person who comes to him seeking purification from inner passion

It is truly awful if one approaches a priest in order to satisfy all this internal hunger, to cleanse the sores of his soul, to get rid of all that inner filth, and yet continues to see afterwards a growth of his inner passions, an accumulation of his existential emptiness and anguish and a spiritual death which envelops him even more. Then he is wounded more deeply and agonizes much more.

4. MEANS OF THERAPY

Having seen who the therapist should be, and who the sick man is, we will go on to study the means of therapy that are employed by God through the experienced and able therapist.

In the above section we briefly mentioned the need for an able and experienced priest-therapist, who has previously been cured himself. Since therapy, the therapists and methods of therapy overlap, we will inevitably return to some points we have already made.

Firstly, a genuine and unadulterated spiritual father-therapist is needed so that a suitable therapeutic method can be employed and put into practice. The therapist himself must know his own self very well and must have boundless love for the person undergoing therapy, the Christian. The Christian should be glad even at the simple presence of his spiritual physician. Ultimately, the very existence of the therapist benefits the person who is spiritually sick. St. John writes, "when a sick man sees his physician he rejoices, even though he may perhaps gain nothing from him"(10). Certainly, this means that the therapist must have clear knowledge that "the sin that the superior may commit in his mind" is worse than the sin committed in actual deed by the disciple (60). This knowledge will make him very discerning and therapeutic, otherwise he will impose unbearable burdens.

It is not easy to cure the sick. It needs love, spiritual courage, because in the course of therapy many problems arise and require delicate handling, precisely because one is dealing with the delicate, sensitive realm of man's soul, with its very fine touches. For this very reason the therapist must show "zeal, love, fervor, care and supplication to God, towards the very misled and broken" (79). Here the sick man is called "broken" and this is why delicate intervention is needed. The therapist must have the ability not only to expose external wounds and traumas, but also the cause of the sickness of his soul that does not show on the outside (22). Moreover he should discern those who approach him in accordance with their desires, i.e. what they want from the doctor. The spiritual therapy should be undertaken once he has distinguished between "genuine children," "children from a second marriage" and "children by slave girls" and "others that are castaways." This is because they are not equally sick people all that come forward to seek the same thing. Consequently, this discernment is absolutely necessary for this intervention that takes place within the realm of the soul. Furthermore, as St. John underlines, the complete self-offering of the spiritual father-therapist is required for this highly responsible task, namely, "a laying down of one's soul on behalf of the soul of one's neighbor in all matters." This responsibility is sometimes connected with sins of the past and sometimes with the sins of the future (57). Therefore, from this task alone it can be seen that the therapist must have great spiritual strength. "Before all things, O venerable father, we have need of spiritual strength" because it will be necessary "sometimes to hold the children by their hand and to lead them in the right way and sometimes to raise up the very small and very weak children upon our shoulders" (93). Thus, the work of spiritual fatherhood is weighty, delicate, definitive, responsible, and sacrificial.

Certainly, we should also recall here that the work of the spiritual father and therapist is not centered on man and does not take place independently in a vacuum. It requires the coordination of Divine Grace with the patient's free submission. The healing of man's spiritual wounds is not effected by human counsel and laboratory methods but by God's energy and the synergy of the spiritual father-therapist. Throughout the whole of St. John of Sinai's text there is discourse on prayer, on God's intervention and on the fact that the real therapist is God Himself since all human beings are God's children. The archetype of men is God and not man. Nevertheless, God cannot act, nor can he help the able and experienced spiritual father if the sick person does not cooperate. In Orthodox therapeutic science, everything happens with free consent, never by force and constraint.

Throughout his whole text St. John of Sinai gives great weight to the sick person and to his coming forward completely willingly and without being coerced and indeed to his complete cooperation in his own therapy. Man's freedom is inviolate. He points out somewhere that as a pilot cannot save the ship without the cooperation of the sailors, so a physician cannot cure a sick person "unless the patient first entreats him and urges him on by laying bare his wound with complete confidence" (36). That is to say, the following elements are needed for the cure: the patient's confidence in his therapist, his free consent to his assistance and, of course, his voluntary uncovering of his wounds. There is absolute need of free movement in all this activity. Since, the salvation of those "patients who do not cooperate" themselves is really impossible (64). At the same time there is a situation where a sick man feels his timidity and his weakness and therefore wholly submits his will to the experienced therapist, but in this case his free self-offering must be laid down as precondition. People in this category seek to be "cured by voluntary constraint" and, naturally, in this situation St. John of Sinai advises the physicians to obey the free offering of the patients (31). It is clearly understood, however, that therapy cannot be achieved without the free consent and self-willingness of the spiritual children and for this reason "a genuine son is known in the absence of his father" (58). Besides, when we talk about cure in the Orthodox tradition, we mean the proper regulation of man's spiritual organic structure so that frequent intervention and dependency is unnecessary. Man, freed from the slavery which created things and the world of passions impose on him, travels on the road of continual ascent and progress.

Another consequence of the free consent that a sick patient should have has to do with his manner of confession. In other words, an important means of therapy is the Sacrament of Confession, according to which the sick person reveals his internal wounds by his completely free submission. St. John of Sinai is particularly insistent on this topic. We know very well, of course, that there are two kinds of confession, namely the revelation of the soul's wounds, so that therapeutic intervention can take place, but also the disclosure of inner thoughts, so that man can gain spiritual direction.

St. John submits some very important information about confession. Firstly, confession should occur with the absolute honesty and freedom of the patients, since effective help can then be offered. "For they receive no little forgiveness by their confession to us." This is because, as the Saint counsels, even if the spiritual father-therapist has the gift of clairvoyance and therefore recognizes the wounds of the soul, he should refrain from revealing them and should let the person who has come forward confess them himself. In such a case, says St. John, "urge them to confession by means of enigmatic sayings (i.e. ill an indirect way)." Furthermore there should be continual interest after the confession since, as St. John teaches, we must allow them to have greater openness after confession too. However, the spiritual father-therapist must prove himself to be an example of humility to the patients, except, of course, in the case of disobedience when he must teach them to be respectful towards him (84). The text clearly shows that confession is not an easy thing, but it properly takes place within the framework of freedom, love, humility, respect and patience. This happens because the revelation of the inner world demands delicate conducts and constitutes a very difficult and onerous task.

St. John gives other detailed instructions about this perspicacious and responsible mission. The sick person should be exhorted to reveal precisely the kind of sinful act that has been committed. This is required for two reasons: firstly, so that he will not become too bold before his therapist and secondly, so that his therapist's love may be aroused through his knowing of the sins that have been taken on (45). Here it is clear that the relationship between therapist and patient is quite delicate and there is a chance that the potential for open dialogue between the two could be lost either through much boldness on the part of patient or through lack of love on the part of the therapist. Therefore, much care is needed in order to guarantee both the respect of the person who is being cured and the great love of the therapist towards this person.

Yet, even this confession of inner wounds "according to kind» has its own limitations. The therapist should not violently and forcibly intrude into the inner state of a patient's personality. There is no need for a detailed examination of the patient's personality. St. John says: "See that you are not an exacting investigator of trifling sins. thus showing yourself not to be an imitator of God» (49). God does not abolish man's freedom and does not examine the details of one's life. Consequently, the therapist should also work within this framework, otherwise he runs the risk of losing his imitation of God, and failing to do his work according to the will of God. Furthermore, the spiritually sick man should not give detailed descriptions of his carnal transgressions, as he should do in other cases. In other words, for other sins full descriptions are required because only then the internal causes of actions could be comprehended. For carnal sins, however, one should not be as explicit: "Instruct those who are under you not to confess in detail sins relating to the body and to lust; but as for all other sins. teach them to bring them to mind in detail, both day and night" (61). St. John says this because when a sick person gives a detailed explanation he is somehow indulged and gratified with the recollection, so fine processes and changes are aroused in his inner world.

The therapist naturally underlines the confidentiality of confession, since he is not allowed to divulge to others the contents of a person's confession. The therapist must not disclose the revelations of the soul that others have given to him. He places this on a theological and a soteriological basis. In other words, he explains that on the one hand, God does not reveal the confession He heard, and on the other, because the prospect of divulging this confession creates enormous problems for the salvation of those involved, because in such a case it would "make then incurably sick" (83).

We should go on to examine the ways that a good therapist uses, since there is a difference in those who come to confession, from the standpoint of spiritual age, lifestyle, illnesses of the soul and so on. The experienced spiritual physician should know all that, for otherwise the manner and method of therapy is distorted, man's freedom is abolished.

The therapist must know, "for whom, and in what manner, and when" all the various commandments of Holy Scripture are to be applied (29). The time and way of life of people play an important role in their method of treatment. The Shepherd should be like a general who knows "precisely the ability and rank of every man under his command," because there is a difference in spiritual age and some need milk whereas others need solids, or because this is "a time of consolation" (54). People have many differences among themselves, "for there is much variety and difference between them." For this reason those responsible for this martyr-like service, the cure of men, must also take into consideration "their location, their degree of spiritual renewal, and their habits" (46). The origin of people is different and therefore each person needs to be handled in his own way (44).

A remark by St. John where he says that the therapist should not always work with justice, nor should he take care always to do justice, is important, because not all people can bear the same thing. He presents the way in which a wise and discerning Elder handled the case of two brothers who had apparently quarreled between themselves. One of them was guilty, but was much weaker, and this spiritual father declared him to be innocent. The other brother was innocent, but because he was strong and brave, he condemned him as guilty and this "lest by judging according to what is just the breach between them should become greater." He certainly spoke accordingly to each one in private, especially to the one who was spiritually guilty (80). One sees here that man's treatment does not occur on the basis of courtrooms and the handing out of justice, but on the basis of curative science, i.e. the abilities that each man has.

The knowledge that the therapist should have in order to cure the illnesses of the souls of those who come to him is necessary, because it is closely linked with the therapeutic methods and the medicine that he will prescribe. It does not just require a correct diagnosis or just knowledge of the particular characteristics of each person, but rather requires the correct prescription of the remedies. We will take a look at some of the therapeutic methods an experienced director of souls uses, e.g. as St. John introduces these to us.

The prescription of spiritual medication is closely linked to the suffering fellow heart of the therapist. That is to say the spiritual father and therapist participates in the pain and the spiritual state of his brother. The Abbot should clearly "be disposed and compassionate to each according to his merit." Effective treatment only occurs within the "suffering fellow heart." The other person's pain becomes his pain and he himself suffers with the sick man's condition. It is not a case of objective medicine, but one of personalized medicine. The spiritual intervention occurs in such a way, so that it transforms the deceitful monks into simple ones and not the simple and honest monks into deceitful ones with complex thoughts (95). It demands prudence and discrimination.

In a wonderful text, St. John adapts the instruments used by physicians of his time to treat bodily illnesses to the means of operating on wounds and illnesses of the soul. The spiritual therapist must use a variety of means corresponding to the variety of the people's illnesses. For visible bodily passions he uses a plaster. For the treatment of inner passions which cannot be seen and to purge the internal realm he uses a medical elixir. To clean the eye of the soul he uses an eye salve, and for surgical intervention where he has to clean something putrid he uses a razor or scalpel and knife. He is not content, however, with just surgery and the use of the proper instruments and therefore also uses various instruments and remedies during and after the operation. He uses a sponge, as it were, in refreshing a patient with sweet, gentle and simple words. Again he uses a caustic substance in stipulating a rule and penance of love for a short length of time. Yet again he uses an ointment in supplying words of comfort that relieve the patient, and a sedative in taking up the burden of his disciple so that the disciple will have "holy blindness" and will not see his good works. Certainly there are also cases when the therapist ought to use a knife to cut off a rotten member for the benefit of the other brothers (12).

It is quite clear from St. John's description that there is a variety of medicines and instruments. It sometimes requires treatment, sometimes the discharge of the stench, sometimes it needs surgery and at other times amputation. However, the surgical operation should take place with discretion without hurting the patient.

The medication given to those sick souls should correspond with their spiritual state. He advises that the therapist "should examine the case of each one and prescribe medicines which are suitable." For those who have sinned a great deal he should give comfort so that they do not fall into despair, for the proud and selfish the way that is straight and narrow (32).

For some the therapist should pray with great vigilance (8, 9), to others he should offer his words and teaching (6), while he will reprimand others and cause them a little pain, "lest from accursed silence his sickness be prolonged or he should die" (26, 27). Others gain benefit from "remembrance of one's departure" (81), others benefit from other things, and the community benefits from "dishonor" that is the humiliation of the patient (82), while some others need heavier penance (58). The therapist gives to each according to what will benefit him spiritually. The manner of prayer that he determines for each person is different. Even the prescribed diet is different. Indeed, using the conduct of an experienced Abbot as an example, he says that he preferred to drive a man out of the monastery, because in that way he would benefit more, rather than let him remain in the Monastery and keep to his own will, in the name of charity and condescension (94).

Each person is helped and benefits differently. In one person when divine love has been ignited fear of harsh words no longer hold sway. In another, the presence of the fear of hell created patience in all labors, and in others the hope for the Reign of God has led them to the disdain of all earthly things (34). It is clear from all the aforementioned that the way of therapy is a diakonia or service of crucifixion and not a superficial activity. The distinctive particularity of each person, but also of their disposition and make up require different approaches. They mainly need a perceptive, sensitive, experienced spiritual physician who will not only make a correct diagnosis and give correct treatment, but above all is ready to suffer with the patient, to feel the hurt and the patient's pain not only within his own soul but also upon his body. He should surely be ready and willing to take up the cross of spiritual direction. Spiritual curative science is not a cerebral duty but a life of martyrdom and witness, according to the example of Christ and of all saints, like the Prophet Moses who painstakingly led a stiff-necked people.

5. PRESUPPOSITIONS OF THERAPY

So far we have spoken about what spiritual sickness is, who a suitable therapist is, what cure is and, of course, how it is achieved. We have yet to underline that man's cure is found not just in some psychological support and some individualistic practice, but first and foremost in man's journey from isolated individuality towards a personal relationship. This is a journey from self-love to love of both God and man, from self-seeking love to self-denying love. It is precisely for this reason that cure takes place within a particular spiritual climate.

The Church, which is understood not only as a family, but also as a spiritual hospital, is the most suitable place to practice therapeutic treatment. We have already underscored that illnesses of the soul are a result of the loss of man's relationship with God, his fellow human being, his own self and the whole of creation. This is accomplished within the Church.

The whole of the text by St. John of Sinai that we are examining presupposes a coenobium, a monastery. It is addressed to an abbot, who is the Shepherd, and whose work is the cure of the physical and spiritual passions of the monks. We do not need to spend long studying this point because a simple reading of the text "to the Shepherd' confirms this.

I would just like to point out that St. John talks about taking can in the reception of the "sheep" (89), so that they will take their place in the flock with predilection and zeal for their salvation. It is also necessary for the entrant to be of a suitable age, so that he will not regret it later, after receiving the monastic habit. However, even though the monks live in a specific community, the possibility for freedom should still exist in accordance with age. The superior should be careful about this matter because "the conditions and dwelling places of all of those under us differ depending on their years" (69). Additionally, special care is needed, because when the fighters live with the indolent many different problems arise (63).

Therefore, the community, i.e. the coenobium or the Monastery, is understood as a therapeutic community into which a man enters in order to be cured and to become a person but also to acquire essential communion with others. In this therapeutic community there is a specialist therapist, but also other spiritual brothers, who help the brethren living there.

The epicenter of the community, however, is not man, since the community is not constructed on just a man-centered basis. Its center is God, since that Shepherd-Abbot carries out his mission with the strength and energy of God. Thus, the community that St. John of Sinai has in mind is the monastery. Its center is the church building, the Holy Temple, where the Divine Eucharist is served. It is the most important act, because by it we attain unity with God and with our brethren even with the whole of creation and, of course, with the whole act of worship taking place in the church. At some point St. John mentions that a certain man beloved of God told him that, "God always rewards His servants with gifts, yet He does so especially on the annual festivals and the feasts of the Master" (17). Here it is clear that it is not a case of humanistic cure, some psychological balance, but of gifts that come from God and indeed during the great feasts of Christ the Master. A presupposition of this is the worshipping assembly of the members of the Church. Indeed, man's journey towards his union with God is acknowledged through the image of the Divine Eucharist (93).

The existence of the community, the serving of the Divine Eucharist and of worship are inseparably linked with another necessary element of man's cure and that is the doctrinal truth of the Church, the doctrines and what is called the faith. St. John would advise the Shepherd "Before all else, leave the inheritance of dispassionate faith and the doctrines of piety to your sons" (97). Orthodoxy is made up and composed of dispassionate faith and pious doctrine. By this Orthodox faith one leads not only his own spiritual children to the Lord, but also his spiritual grandchildren. Indeed, this is the greatest spiritual inheritance.

Consequently, these three factors are the requisite preconditions for man's cure, namely the Community-Church, the Eucharist-Worship and Orthodoxy (dispassionate faith, pious doctrine). Even the hesychast and hermit is not separated from the community, because either he has lived in a community beforehand, or, indeed, is inspired by one. This is because he lives with community spirit, inasmuch as he loves God and is having communion with Him, with the whole world, and of course with the Eucharistic Body and Blood of Christ which he receives at the Church. The fact is that when man manages to appreciate the depth of his being and the evil found within him, indeed, when by God's Grace and the aid of an experienced spiritual physician man's soul is cured, then he comes to know the depths of evil but also the heights of redemption. It is enough if someone comes to the point of realizing the fall and the resurrection within the bowels of his being. Then he knows what the whole world is all about.

CONCLUSION

Man's cure is the most important work that can be accomplished on the earth. St. John would say: "Therefore, O blest man, do not call blessed those who make financial offering, but rather those who offer rational sheep to Christ." There is no gift more acceptable to Christ than bringing to Him "rational souls through repentance." This is because the whole world is not worth as much as one soul, since "one passes away while the other is incorrupt and exists and abides" (90).

The therapist with his purity, which is not his own doing, but a gift from God, soaks up the filth of others, proving himself to be "a fellow laborer of the bodiless and spiritual powers" since that is their work (78).

Today people ultimately seek out their cure as described and presented by St. John of Sinai and as offered by the Orthodox Church. Moreover, when man pursues justice, peace, equality amongst people, within his very depths he seeks cure, that is the correct relationship with God, with others, with himself and with creation. Grievances, complaints, continual grumbling and gripes arise because at his very core man is not living his potential fullness. Certainly what is necessary for this work is the presence of a sensitive, patient, spiritual father, who is a free soul himself, has absolute respect for fellow man's freedom and can truly lead to freedom of spirit and not to self serving aspirations.

NOTES

[ 1 ] English quotes are from the Ladder of Divine Ascent by 51. John Climacus, translated by Holy Transfiguration Monastery, Brookline MA, 1979, with some adaptations.

[ 2 ] Archim. Hierotheos Vlahos: Orthodox Psychotherapy, trans. Esther Williams, published by The Birth of the Theotokos Monastery, Greece 1994.

- Hits: 8056